With reporting from Max Ridenour.

Neighbors, organizers and camp residents gathered early last Friday morning at Camp Nenookaasi, the largest homeless encampment in Minnesota, for a potluck breakfast designed to introduce the community to Nenookaasi and provide a meal to the residents.

Camp Nenookaasi, named after the Ojibwe word for hummingbird, has been evicted three times in the past month by the City of Minneapolis. Despite the repeated evictions, new iterations of the camp continue in different plots of land around South Minneapolis.

Nicole Mason, a head organizer of the camp and a ‘mamma bear’ to the residents, says that the camp has helped over 100 people find housing and over 30 find treatment for substance dependence. Despite her ultimate goal being for everyone in the camp to find the resources they need to be housed, she says the resources have not been sufficient.

“Everybody here is on some type of housing list, waiting for someone to come and take their number,” Mason said. “Nobody comes [to the camp] and asks, ‘do you wanna come to treatment?’ They’re gonna stay in the same predicament if we don’t help them out.”

Camp Nenookaasi is a space that predominantly unhoused Native residents rely on, and Mason incorporates reclaimed healing methods as part of taking care of camp residents.

“Our traditions and culture were ripped from us without our consent, and our people haven’t been the same. This wasn’t that long ago, and so our people have been traumatized from that for generations on … we have to learn, and that’s what we’ve been teaching here is to go back to the old ways, and being kind and loving to one another, we have to go back to that, everybody does, not just Natives,” Mason said.

Though Mason’s ultimate goal is for each resident to find the support they need to leave the camp, she also emphasized the positivity of Nenookaasi for the residents, and for herself.

“[The residents] have built a community and a family, and breaking up family or community is hard,” Mason said. “They’ve become my family as well, and that’s all I can help people understand, is that they’re really wonderful people, they’re human beings, and I think a lot of people make a lot of assumptions based on what they read or what they see on social media, but it’s not all correct.”

Julie Cross is a volunteer with Mino De’e, a group that collects and serves food donations for the camp, and has witnessed the sense of community at Nenookaasi and the effect the evictions have had on that spirit.

“[Watching the evictions] is really, really rough,” Cross said. “When the residents were at the first camp, what I witnessed was a community … and then they got evicted, and you could see the wind knocked out of their sails, and then came the next one and they’re back to being defeated again.”

According to the City of Minneapolis’ website, “encampments can create health and safety risks for the people living there, as well as the surrounding community. The City must balance the needs of unsheltered individuals, community members, and business owners in its response.”

Despite citing concerns for health and safety, volunteers like Cross have their own thoughts about what is motivating evictions.

“When [the City of Minneapolis] evict a camp, I always refer to it as ‘they’re in the wind,’ you don’t see them, and I do feel that is a part of Mayor Frey’s objective is, you aren’t aware as much of the homeless situation when they’re unable to be encamped,” Cross said.

Neighbor of Camp Nenookaasi, Liseli Polivka is one of many nearby residents who have embraced Nenookaasi into the neighborhood, with hopes other community members will do the same.

“What we’re doing to homeless people right now in Minneapolis seems cruel,” Polivka said. “The scars they’re leaving all over the city with the fences … my whole neighborhood, every couple blocks there’s a chunk of Earth covered in rubble with a fence around it, now no one can use it.”

Camp Nenookaasi is always accepting donations for basic needs, but Polivka encourages people to visit the camp even if they do not have the resources to provide donations.

“If you can just come down and say hi, because that’s what I think the residents want more than anything, is just to be seen,” Polivka said.

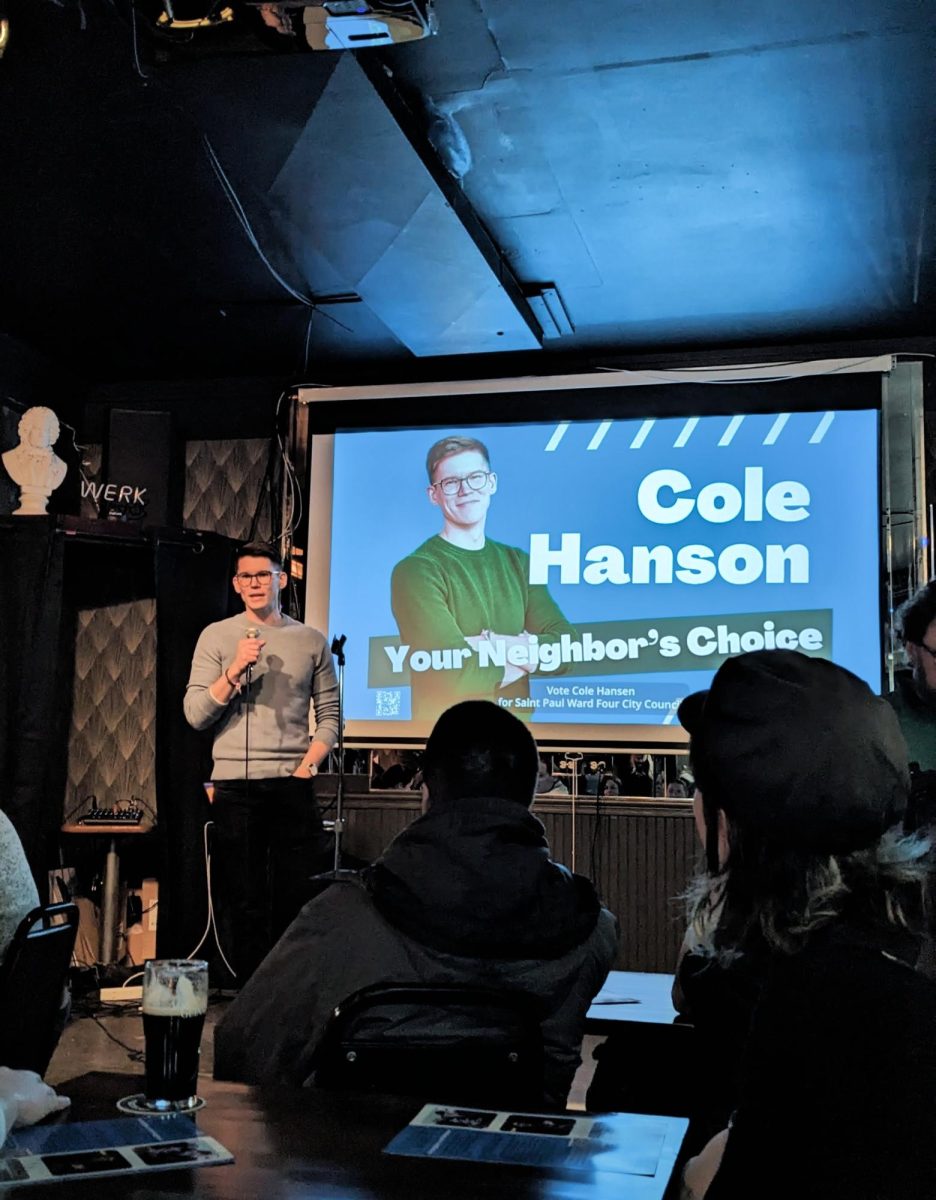

Minneapolis City Council Vice President Aisha Chughtai and City Council Members Aurin Chowdhury and Jason Chavez proposed three new ordinances on Feb. 8 that hope to directly address the tensions between the city and encampments in Minneapolis.

The Safe Outdoor Space ordinance is being referred to the Business, Housing and Zoning meeting on Feb. 13, while the Humane Encampment Response and the Encampment Removal Reporting ordinances are being referred to the Business, Housing and Zoning and Public Health and Safety meeting Feb. 14. Camp Nenookaasi organizers released a statement on their Instagram regarding the ordinances, establishing that while the ordinances affect all unhoused people in Minneapolis, the attempt from the council members is an appreciated attempt at change.

“We’re thankful for courageous Council Members who are taking a lead addressing a complex issue with creative solutions that work towards repair rather than compounding harm and generational trauma,” the Camp wrote on their Instagram page (@campnenookaasi).