Throughout American history, Indigenous communities have been ostracized and marginalized systemically in every regard. Now, in the 21st century, higher education is working towards repairing bonds with the communities that once occupied the land the institutions are built upon. However, without action to fortify the attempts at reparations, higher education’s outreach — through the likes of land acknowledgments, among others — may conduct more harm than good.

Member of the Seneca Nation of Indians of Western New York, Assistant Vice Provost of the University of Minnesota’s Graduate School Diversity Office Dr. Cori Bazemore-James, who recently spoke as the keynote speaker during the Social Justice Symposium week, highlighted this very sentiment, providing essential information to the history of higher education.

“Higher [education] was created for two reasons. One was for wealthy white men to gain a higher status and roles in the clergy. The second goal was to Christianize and civilize Native Americans,” Bazemore-James said.

History Department Chair Kate Bjork echoed Bazemore-James’ statement, noting the importance of viewing complex history through both a historical and contemporary lens.

“There’s a longer historical presence of indigenous people and Dakota people here, but there’s also contemporaneity. I think this is a thing we don’t pay attention to. I’d say this is a function of the way that we tell stories about history, that they can’t be complicated enough to accommodate simultaneity,” Bjork said.

One such way that higher education employs contemporary solutions is through land acknowledgments. Land acknowledgments first originated in Canada and have slowly spread to the United States and beyond. They must be, however, backed by substantial action.

“A statement like that is hollow, it doesn’t mean anything if there’s no action behind it. So there’s got to be other commitments,” Bazemore-James said.

Member of the White Earth Nation, Minnesota Historical Society Program and Outreach Manager Rita Walaszek Arndt spoke about this very idea, explaining the need for continued support for Indigenous students, faculty and staff, particularly when it comes to higher education.

“There’s still places where there isn’t necessarily … welcoming spaces for underrepresented groups. So [land acknowledgments are] still doing the work that [they were] intended to do when they were created,” Walaszek Arndt said.

Tokenism refers to the concept of relying on a small group or single individual of a certain identity to represent the entirety of the identity for the sake of diversity only. Dr. Bazemore-James emphasized the importance of moving away from tokenistic practices in favor of equitable and inclusive ones.

“I don’t think anyone thinks it’s important. I don’t think people recognize the need to have good relationships with tribes on the federal, state and institutional levels. They very much want to show they have diversity,” Bazemore-James said.

Although a lack of meaning and initiative from institutions of higher education may require more priority, it is equally important to bring awareness to the reparations that are successfully being made.

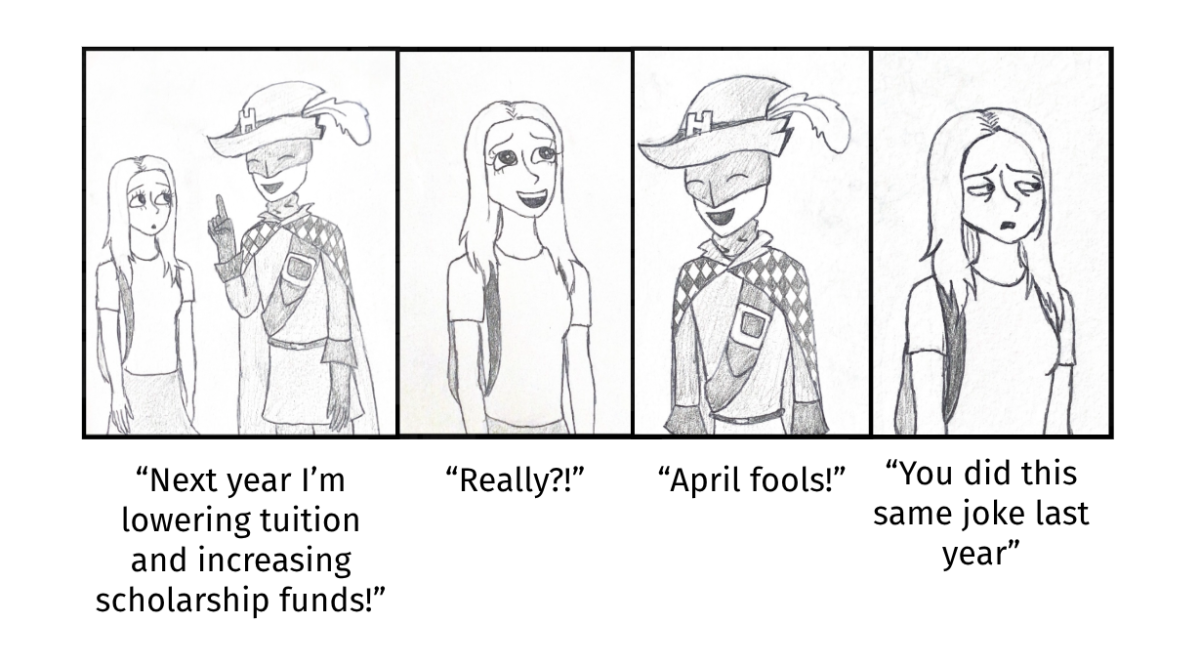

“They now have a tuition program for Native students to be able to go [to the University of Minnesota] for free. … But what’s interesting, it’s only [for] Minnesota tribes. … There are Dakota who were here that were exiled and so they would not be able to do that,” Walaszek Arndt said.

In addition to tuition programs, Dr. Bazemore-James places importance on creating connections with leaders from local tribes and leaders from the institution as a way to put the institution’s money where its mouth is.

“[A tribal liaison] is meant to be more externally facing from…the institution they are connecting with…trying to bridge that relationship between the tribes and the institution,” Bazemore-James said.

Although it is crucial to remember those who came before us in order to learn how to move forward, Walaszek Arndt reinforces the idea that history must also be viewed in a contemporary context, seeing Indigenous communities exist within the scope of the modern world.

“We exist, we still exist. We’re still in these spaces. Just because you’re on that stolen land doesn’t mean we’re not here,” Walaszek Arndt said.

Stolen land, empty words

Alex Bailey, Junior News Editor

April 23, 2024

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover