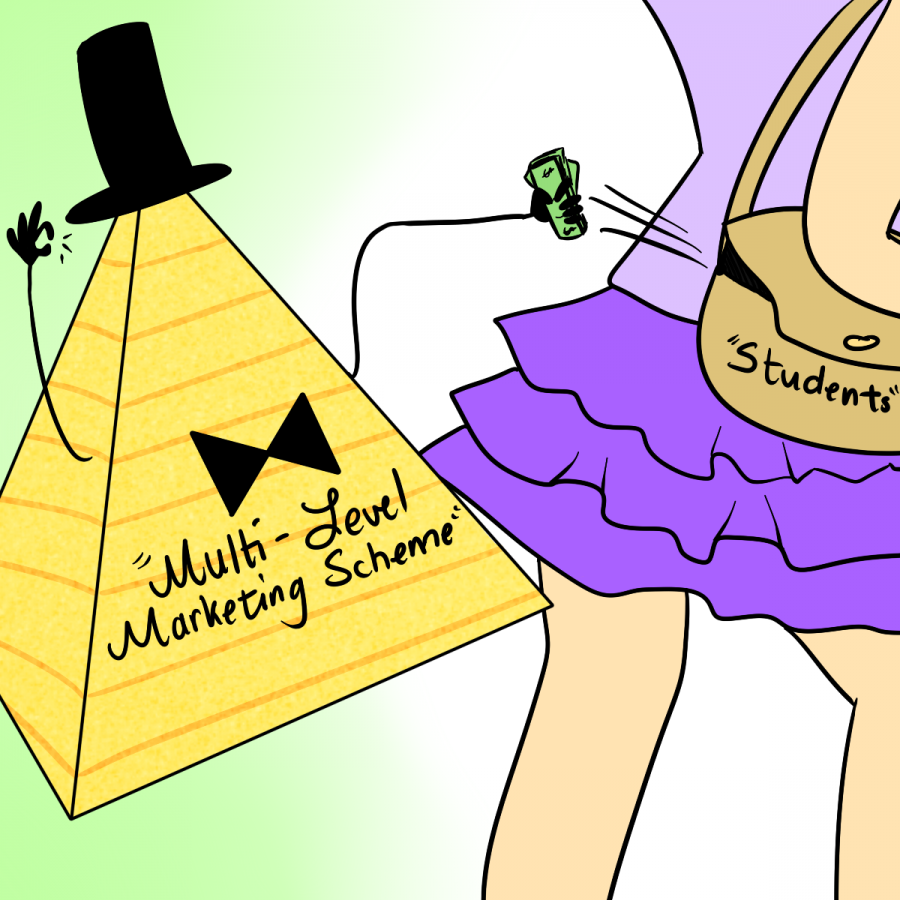

Students beware: multi-level marketing scheme detected on campus

Students and staff discuss what to look for to avoid getting scammed.

December 10, 2014

Daniel McKenzie is a junior studying economics and business. He was in Anderson Center around midnight two to three weeks ago. In the middle of a late-night study session, he saw three gentlemen from Amway pitching to an unnamed, first-year student. “What informs my concern and knowledge,” McKenzie said, “is that I had a lot of friends coming out of high school that became involved with Vector.” Vector, like Amway, Maleluca, Herbal Life, and others, is a multi-level marketing company, or a company that is alleged to be a pyramid scheme.

Pyramid scheme fraud, according to the FTC, is the least reported type of fraud in the country. “These companies sell the process as a part time job; as supplemental income,” McKenzie said. And with college students being new to the labor market it can be harder for them to vet the fallacies within these multi-level marketing opportunities. He was alarmed by Amway’s presence on campus.

Making sure to not call these companies’ independent operators “employees,” McKenzie outlined the basic pyramid structure this way: “An operator will show you that if you can recruit three people to sell [the companies’] products for you, and those three people can all recruit three people to also sell the product, then the graphical representation of this structure begins looking like a pyramid.” This schematic, according to McKenzie, is one of the signs that a student is being pitched a multi-level marketing scheme.

Take Amway for instance. According to McKenzie the company has been around since the 1950s and had its first appearance in court in 1971. In 2010 Amway settled a class action lawsuit out of court for 56 million dollars. “If there was ever a red flag,” McKenzie said, “that one would be the one.” Also in 2007, The Times of London investigated Amway. In the process it was found that ninety-percent of Amway recruits made no profit. Amway reps in India have, recently, been jailed.

Stacey Bosley, Assistant Professor of Economics not only specializes in multi-level marketing business opportunities; she has also seen the effects of multi-level marketing schemes firsthand.

“I had extended family in the nineties that was heavily involved in different marketing companies,” Bosley said. Besides the basic structure or shell of these types of companies, she was introduced to the economic, social and psychological ramifications to those associated with these “opportunities.”

There can be psychological ramifications. Truly believing the multi-level model is one that fosters success if only he/she will work hard. Socially, “employees” may suffer avoidance or snuffing as friends and family dislike feeling pressured to buy products they don’t want. And the economics, staggeringly, is that even high earners in these companies are in the red come tax time.

How can one stay ahead of these types of companies? According to Bosley there is a fairly straightforward list of warning signs:

Can you understand the compensation plan?

Recruiters won’t tell you what the company or the opportunity is when they are initially trying to recruit you.

Recruiter/company emphasis will be on recruitment, not product.

Company rhetoric may entice it’s employees to finance their investment/product purchases with debt.

Direct selling: selling that takes place away from a fixed retail location.

Can you understand the compensation plan?

The compensation plans are extraordinarily complex, Bosley explains. “All you see are these bonuses and infinity bonuses, and the possibility that if you recruit three and they recruit three, then your income is going to explode.” These companies use income generators to “help” prospective recruits see those riches.

At recruitment conventions the company will bring bonus earners up onto a stage where they show off big checks. “But most often,” Bosley said, “achieving even a reasonable sized check has you in the red.” She explained that some high level earners found they were actually losing money.

This diversionary tactic is called gain framing. “When the focus is framed around the gains it is easy to minimize the conversation of losses,” said Bosley. The losses accrue because there are purchases of inventory, costs of going to conventions, training materials, joining fees, minimum monthly purchases and many other costs that the recruit does not take into account.

Recruiters should be able to tell you what the company or the opportunity is when they are initially trying to recruit you

Recruitment starts with someone you know, McKenzie explained, a family member, a friend, a friend of a friend, or even someone who knows your name and ends up involved with the company. “It was someone I had lost contact with from high school that called me,” McKenzie said. “I asked questions and the person told me, ‘Just come to the office, just come to the office.’ …After a little digging I found out this individual lost five thousand dollars during their involvement with Vector.”

But if one misses that they aren’t being told the company name on purpose, the pitch itself holds others. McKenzie paraphrased the pitch he heard in Anderson, “We’re going to get a young team together and be dynamic and tenacious and take the campus and then the world by storm.” The way he was pitched was different.

He was invited to a convention. McKenzie explained that the convention took place in a rented room in a posh hotel. There was an air of success. Everyone wore their best clothes. There were snacks and refreshments. “It makes you feel special,” he said.

Recruiter/company emphasis on recruitment, not product

The nature of the sales experience, Bosley explained, is tilted. “If a company gave you a job in sales you would get a territory,” Bosley said. “And it would be staked out. And then you would have market protection from saturation. But these companies do the exact opposite.” The incentives are to recruit people close to the individual, thereby saturating the markets to which you should be selling.

McKenzie explained a saturated market this way: American Eagle would not put 12 American Eagle stores on the same block. All those other stores selling the exact same product would cannibalize the business. “They do it because they’re not worried about selling a product,” McKenzie said, “They’re recruiting, and not just your neighbor, but your neighborhood.”

When researches have been able to get their hands on data from these companies it is often shown that distributor turnover from year to year is near 90 percent. “The argument from those companies,” Bosley explained, “is that the buyers only wanted the product for a short time and then they were done.”

The real issue, she explained, is that these companies sell their products to independent distributors and do not capture what happens to the product after that.“Imagine, a multi-billion dollar retailer that doesn’t know who they’re selling to,” said Bosley. “We don’t know if [the retailer] sold them, dumped them down the drain, gave them away to his friends, or if he sold them to Mary and Mary paid a decent price.” There is not enough data to determine corporate legitimacy, she reasons, and still the companies exist.

Should not have to and/or should not be asked to finance with debt

According to McKenzie, when students already have excessive loans, one of the worst things they can do is to take out more loans in order to get started in a business venture. “The worst time for a bad decision like this would be when you’re already at a point of financial weakness,” said McKenzie. A lot of these companies sell their business model as a solution to that. It’s much worse for students to get involved in these types of companies because they are already in debt.

He also mentioned that multi-level marketing companies might tempt recruits to investt early by showing those visualization compensation packages. “Fake it till you make it,” said McKenzie. This mentality, for some, adds an air of legitimacy.

Professor Bosley agrees. “That phrase really troubles me,” she said. The only way to lose is to quit is the underlying message, she explained, and it requires investment and it requires belief. The only sure way to succeed is to stick with it, which incentivizes the need to continue. “I have talked to many people whose relatives or friends will still say they failed the business the business did not fail them,” said Bosley.

Direct selling: selling that takes place away from a fixed retail location

An example of this emphasis on retail versus direct selling came from Bosley. She told how Amway had opened a store in the new Met stadium. “There are giant displays of products, beautiful displays,” she said. “But the products aren’t for sale because it would undermine the direct selling markets.” One has to go into another room to learn how to buy the products from an independent sales representative. If one cannot buy it directly from a retail standpoint, Bosley argued, then the business focus is skewed.

Final Analysis

According to Bosley the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has captured a lot of data on these Multi-level Marketing Opportunities. “People get embarrassed and don’t report this,” Bosley said, “because, perhaps, they are ashamed they didn’t succeed, or they might still believe it’s a viable business, or they’re hoping it will catch on soon.” The psychological reasons behind this are varied, the ramifications socially tangible as well as monetary.

Bosley asks students to ask themselves these questions when faced with a business opportunity that sounds anything like the examples above.

When does it make sense to buy a product from someone in your social network?

Why would one buy interpersonally instead of retail?

Where is the commission/compensation coming from, the product or the recruitment?

McKenzie equated the recruitment efforts to his work with the Democratic Farmers Labor Committee. “I would sell this idea of networking with highly active, young go-getters,” McKenzie said, “…setting up rallying meetings to pump everybody up…creating for recruits a new alluring peer group that could hold [new recruits] hostage in an emotional way.” A member would feel bad if they let the rest of the group down, he explained; you don’t want to accuse your “friend” of scamming you once you get really invested.

Both Bosley and McKenzie agreed that the idea of these businesses is to present an earnings package that looks appealing, one that focuses on recruitment through one’s existing social network, while obfuscating the long-term costs. Bosley is currently working with administration to create a panel in spring that will elaborate further the economics, psychology and sociology surrounding these types of business models.