Drawing the Legends

The story behind the animation of some of our most beloved cartoons.

February 9, 2015

If you’ve ever spent a Saturday morning solving mysteries with Scooby-Doo, visiting the Stone Age with the Flintstones, or tagging along on the Yellow Submarine, then you’re familiar with the artistic creations of Ron Campbell. Born in Seymour, Australia, Campbell realized at an early age that he wanted to be a part of the imaginative world of cartoon animation—which led to a career spanning over 50 years, working on some of the most beloved and iconic children’s shows in television history.

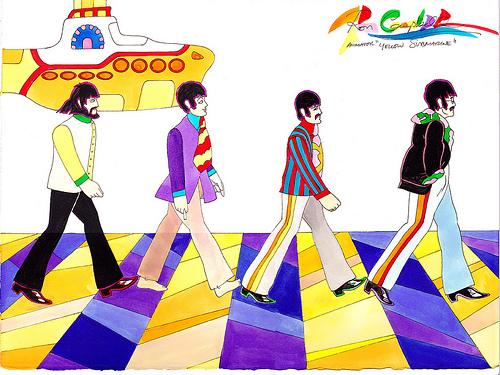

Campbell recently visited the Twin Cities as a part of the 92 KQRS Rock Art Show at the Mall of America, where he displayed some of his original artwork based on the cartoons that defined his career. Much of his artwork features the Beatles characters as they appeared on The Beatles television show and in the film Yellow Submarine—both projects that Campbell played a big role in developing.

The Oracle got the chance to sit down one-on-one with Mr. Campbell. As he painstakingly painted blue stripes onto Ringo Starr’s shirt, he shared some of his incredible experiences from a lifetime of working on productions that would eventually become well-known cultural cornerstones.

Oracle: Which is your favorite show that you’ve worked on?

Ron Campbell: Well, you can’t really differentiate between Scooby-Doo, Smurfette, Chuckie, and the Rugrats. You just can’t. However, the project that gave me the most personal satisfaction was a series of films for children that I produced called The Big Blue Marble. It was a television show in the mid ‘70s on geographic and cultural conditions of children all over the world. We won a Peabody and an Emmy for it, and at that time the Peabody was a very important award, and there had only been two children’s programs that won a Peabody before that: Sesame Street and Captain Kangaroo. We gave the show away to television networks all over the world—it was in 122 countries—on the condition that they put no advertising in the middle of the show, only bookend it with advertising. And in exchange they got the show for free, each network imported in each country. It was the show I was most proud of, but I wouldn’t separate Scooby-Doo from Smurfette. I’m proud of all of those.

O: How did you first become interested in animation?

RC:I was all of six years old. We used to go to the movies on a Saturday afternoon, and that was the equivalent of Saturday morning TV for us. So we’d all go in groups—we’d get a shilling from our mothers; thruppence to get in and nine bits to spend on candy—and Saturday afternoons were devoted to children’s movies. So before the Hopalong Cassidy or Roy Rogers or Gene Autry western came on, with all the bang-bang shoot-em-ups, were a whole bunch of cartoons. Which we adored. And most of them were Tom and Jerry. And little Jerry was always being chased by Tom through all kinds of funny things, and I thought that Tom and Jerry were somehow behind the screen doing all these things. I never connected that ray of light coming down with what I was seeing. So, I thought it would be really really good to somehow make these shows.

Later on, I fell in love with comic strips, and I was not allowed to have comic strips. In those days, parents (like they do now) try to keep children away from the popular culture, with the same motives. In fact, there’d been a silly book put out by Fredric Wertham called Seduction of the Innocent that attacked comic books from every possible angle; convincing parents that comic books were bad for children—including the absurd proposal that Batman and Robin were actually secretly a homosexual couple. And other things like that. Just total nonsense—but taken very seriously. And indeed, Fredric Wertham was so important he was testifying in Congress and all that, about a children’s comic book. Anyway, I was not allowed to read comic books. Since I couldn’t read them, I decided to make them, so that I could read the ones that I made. So I made comic strips. That was my solution to the ban on comic books. And that brought me to drawing…and drawing, and drawing, and drawing…and resolving to finally go to art school to learn how to draw instead of just teaching myself to draw.

I went to Swinburne Institute of Technology in Melbourne, and learned enough drawing skills to do animation: to combine my comic strip passion with my film cartoon one. Then it was 1956, and television had just come to Australia. It’d already been in England since before the war and in America shortly after the war, and ten years later it came to Australia. Suddenly, for the first time, there was a demand for animated cartoons. So I was on the leading edge of a wave— always a good place for a young person to be.

O: How did you get started on animating The Beatles cartoon show?

RC: I’d made television commercials, and then, because I was making successful commercials, a company in New York was looking for a production house that would make cartoons for them that they had sold to American networks—Popeye and Beetle Bailey and Krazy Kat—and they went to England and they went to Holland and they went to Czechoslovakia and they went to Australia looking for production abilities. So I ended up doing the Krazy Kat film for this New York company called King Features Syndicate. I made a bunch of films for King Features that were put on American TV, and lo and behold, I delivered them on time with a satisfactory quality. For the money that King Features paid, they were happy with it. Shortly after that, King Features sold the idea to make a Beatles television cartoon show.

So where would they go to get it produced? This is the way things happen in art. You do a little job, you do it good; you do a bigger job, you do it good; you do another job that’s even bigger still and you do that good; pretty soon you’re hot shit.

So, they sold this show called The Beatles. Now, there’s a little story for you: I got a telephone call in the middle of the night from New York; I’m in Sydney. It’s Al Brodax, the head of King Features television.

He says, “Ron, we’ve just sold a new television show. Would you like to be the director on the episodes we produce in Australia?”

I said, “Sure, Al! Tell me, what’s the show about; what’s it called?”

He said, “It’s the Beatles.”

I paused, thought for a minute, and I said, “Al, what are you doing? Insects make terrible characters!”

I don’t really remember whether he laughed or whether he called me an idiot or what, but he reacted! He said, “Ron, this is a rock and roll group!”

Unfortunately, I’d been so concentrating on how to make cartoon films, such a serious young idiot, that I was a total nerd! I hadn’t been paying attention to popular music at all—if I listened to music, it was Mozart and Beethoven! So I knew nothing about it. However, I agreed to do the show, and I loved their music. Now, I thought some of it was not unlike “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” compared to the complexity of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. But I did like their music, and I still like their music.

O: What was it like working on The Beatles cartoon show?

RC: The show was enormously successful. Some days it had a market share of 66 to 67—which means that of every 100 televisions that were turned on across America, 67 of them were tuned to the one channel that had the Beatles. There are television executives today who would consider killing their mother-in-law for such ratings.

O: Did you work with the Beatles on the show?

RC: No. They gave us the music and went their way. They made music; we made cartoons. I was in Australia doing it; they were way on the other side of the earth. But I met two: Ringo and Paul.

O: You are also one of the original members of the team of artists who created Scooby-Doo. What was that like?

RC: Well, there’s a long story with that. It has to do with show ideas being stolen. Scooby-Doo was actually created by a man who became a friend of mine and a partner, and his name was mud with the networks because of previous disasters. He took this idea of a very big dog that was a coward, and a group of kids who were kind of like Archie and the gang. They didn’t want to deal with him, but they liked the idea. So I helped him do the drawings for that presentation, and developing that show. They said no to him, and then later on, they took the idea to Hanna-Barbera. I ended up helping them do drawings for the same show, but just different, because the designer for it then was Iwao Takamoto. That was the beginning of Scooby-Doo, and how it came about. It’s not really in the books or anything; it’s just my personal knowledge of this. If I ever wrote a book I would tell this story.

O: Why do you think that cartoons like this are such a powerful cultural item?

RC: Because they’re simple. A few lines on a piece of paper can express great anger, great humor, great skepticism. Just a few lines can do it. There’s very little subtlety in animation. Good animators are more actors than they are artists.

O: Since you’ve retired from television, what is that keeps you going with the animation drawings?

RC: Fear of death. Everybody I ever knew that retired died shortly afterward.

All my business life, the audience consisted of numbers on sheets—the ratings of what this show got and what that show got. The people I met were the writers and the actors and the musicians and the artists and animators. When I retired, I had a question as to what I was to do in my retirement, being so scared of death. I decided to do paintings. Then came the question, what shall I paint? I rejected all thoughts of painting portraits or landscapes or flowers, heaven forbid, and decided to just do paintings based on all the cartoons that I spent my life on. Just as Chuck Jones had done before me. He was the brilliant director and animator of Bugs Bunny. When he retired, his daughter opened an art gallery and he did paintings and sold them. They lived comfortably and pleasantly. I thought that was a grand idea. So I did it too.

So now I travel all over the place. I only sell my art directly to people, I do not sell it online, because I believe art can’t be sold on eBay. When a person buys a painting, they should buy it from the painter. They should know the painter. If you’re going to drink wine, it’s a good idea to go to the vineyard that makes the wines you like.

O: A large proportion of the current college generation grew up watching shows like Ed, Edd, n Eddy and Rugrats, along with many other shows you’ve worked on. Is there anything that you hope they took away from watching these cartoons?

RC: The last show I worked on during the last years of my career was Ed, Edd, n Eddy. I always found the show a little bit vulgar. I did not really like all the spits and the splatters and bathroom humor; I’ve never liked that kind of thing. But I recognized that I was making a cartoon for barbarians. Barbarians who multitask—no doubt sitting on the floor in front of the television, with their homework to their left, some comic book to their right, some computer game in front them, and a TV set above them. And the only way we could draw their attention was to have something splatter and explode. That’s what I thought about Ed, Edd, n Eddy. However, I really did like a lot of the humor that was in it. It was a character-driven show, with terrific characters, and that is why I worked on it for so long. So any failures in the culture of the audience, I take full responsibility for and extend my apologies.