I’m not like other girls

How pick-me girls have perpetuated internalized misogyny.

February 24, 2021

Sound carries strangely in the Heights — bouncing off the brick walls and around the odd angles of the French casement windows, cracked to let some fresh air in. Sometimes little snatches of conversation will drift into my dorm from some unknown location; whispers in the wind.

I remember one conversation that I overheard late one October night this school year. A girl was talking to someone (presumably her boyfriend) on the phone.

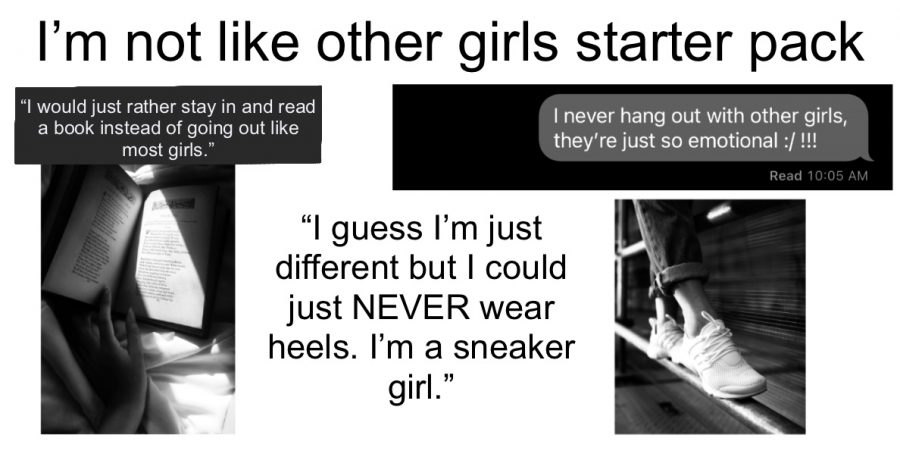

“Yeah, she’s getting all dressed up and everything now…. No, no you know me, I’d rather stay in and read on a Friday night. Yeah, I just don’t see the appeal of all that.” The sentence was punctuated with a snide laugh.

I wrote the conversation down at the time because it was an almost cartoonishly real example of the not-like-other-girls trope, but I remembered it this week when one of the Oracle’s editors suggested that I write about pick-me girls.

For those of you who may not be familiar with the term, a pick-me girl is a girl whose desire for male approval causes her to reject and even condemn modern femininity. Pick-me girls do things like going out of their way to point out that they’re not wearing makeup when others are, start ostentatiously cleaning and cooking during a party while making “I belong in the kitchen” jokes or say things like, “I never hang out with other girls, they’re too emotional!”

The advent of social media platforms (TikTok and Twitter in particular) has exponentiated the use of comedic stereotypes like the pick-me girl, the Karen and the toxic indie boy. We could discuss how categorizing people like this, in general, is potentially dangerous. But frankly, it’s hilarious and thus unlikely to stop any time soon.

Instead, it can be interesting and useful to break down individual stereotypes and examine them and their implications as social and cultural indexes. The pick-me girl is a phenomenal example that speaks volumes about our current social climate.

The driving force that leads to the pick-me lifestyle is internalized misogyny. Raised within the confines of the patriarchy, a fledgling pick-me comes to understand that masculinity is valued above femininity, and, in a desperate bid to distinguish herself from other women subjected to the patriarchal regime, she attempts to subvert her femininity entirely.

This ends up manifesting itself in them shaming other women for their social or sexual liberation. Instead of standing in solidarity with other women who might have different lifestyles than them, pick-me girls belittle and degrade them to stick out from the crowd.

This attitude is frequently accompanied by a strange ride-or-die mindset. “Men make mistakes, build them up” is all well and good until lines get crossed. Chronic forgiveness or letting people get away with doing bad things because “men make mistakes” can lead to things like a couple ending up in an endless cheat-and-forgive cycle in which neither of them are happy.

Another problem that this perpetuates is male entitlement. Pick-me girls set standards for women in relationships that aren’t just antiquated, but entirely unrealistic. Women shouldn’t be expected to stop wearing makeup or stay in with their man every night cooking and cleaning, or forgive a man who cheats.

Platforms like TikTok certainly caricaturize girls like this, but as I learned from my open window, they’re definitely out there.

Here’s the thing: there’s nothing wrong with not wearing makeup. There’s nothing wrong with staying in every night and reading. But don’t expect all other women to do the same, and certainly don’t shame them for doing otherwise.