Review of The Electrical Life of Louis Wain

The 2021 film “The Electrical Life of Louis Wain,” directed by Will Sharpe, conveys the life of the highly influential English artist, but is also sympathetic to his mental health struggles. Wain was not only ahead of his time in artistic style, but also in his attitudes about some of our favorite furry friends today.

November 24, 2021

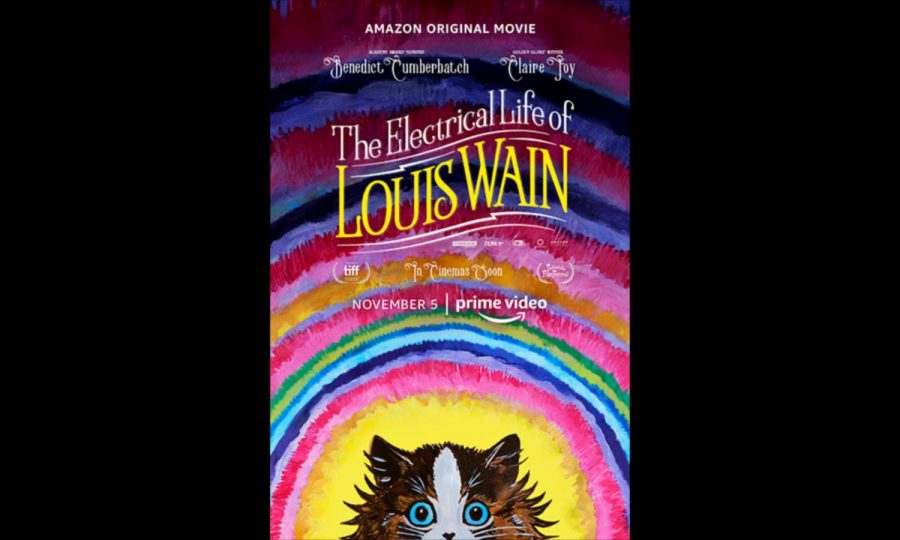

Mental illness, art and cats. These are some of the first things recalled when it comes to explaining the life of Louis Wain. The newly released film “The Electrical Life of Louis Wain” takes care to ensure these themes are captured and that the eccentric, but often troubled psyche of Wain is portrayed in all of its complexity. Of course, the film is not an exact retelling; Wain—played by Benedict Cumberbatch—was born in London in 1860, and beyond his long line of artistic works, there is no perfect source to illustrate his 78 years of life.

What is known is that Wain was the son of a French mother and a father who traded textiles to support both them and his five younger sisters. The film begins once Wain’s father had already passed and the 20 year old male—who was working as a freelance artist mainly drawing dog portraits—is left as the only candidate to head the household. The narrator, Olivia Coleman—who throughout the film reminds the audience that this society is in fact, outdated—comments on the failure of this patriarchal default, as Wain has a remaining parent and a more capable sister who have no choice but to rely upon him.

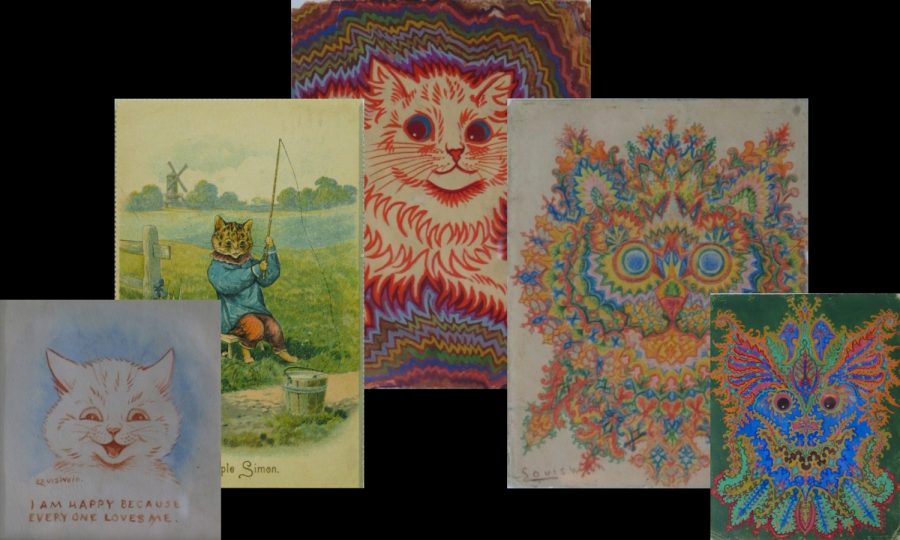

At first Wain’s life begins to look up, with a happy—although greatly scrutinized—marriage to his sister’s governess Emily Richardson, played by Claire Foy, and a new position as an artist for The Illustrated London News. Unfortunately, Richardson is diagnosed with breast cancer, which she passes from just three years into their marriage. Although entirely devastated, Wain finds comfort in the couple’s black and white cat, Peter, and begins to draw the animal almost exclusively, often in anthropomorphic form, taking part in regular human activities. For a Christmas special for the paper in 1886, Wain drew a spread of 150 cats, and his work began to grow a cult following.

The real life Wain has received credit for the normalization of cats during his time—who carried a stigma of being hostile to humans and making bad pets. He even served as the chairman of the National Cat Club and was involved with a number of animal charities. However, Wain’s mental health was steadily deteriorating. This is captured in the movie with cinematic shots portraying his assumed point of view; hallucinations of water filling rooms and crowds of people appearing as cats themselves.

For a long time, it has been claimed that Wain suffered with schizophrenia, and his artwork has been used in psychology textbooks as a way to show the general progression of the condition—although his earlier works were more so fantastical realism, he went on to experiment with abstract, cubist and even psychedelic styles. However, this timeline has since been disputed, as Wain did not date his works. Some have also suspected that Wain may have had Autism Spectrum Disorder. Whatever the case, Wain would experience intense nightmares and anxious breakdowns, leading his sisters to commit him to a mental hospital in 1924.

The first time Wain is institutionalized, the building is shown to be somewhat rundown, and although he expresses sadness at no longer being unable to see much of the world, there are no outright atrocities shown. Following crowdfunding efforts from his fans, Wain is later able to be transferred to a nicer facility in the countryside, that even had cats.

The film is detailed in its portrayal of a suffering man, but does not thoroughly delve into the social and systematic oppression individuals with mental disorders and disabilities suffered at the time. Those around Wain most often perceive his socially awkward nature as charming, although he is often financially taken advantage of, due to his failure to copyright his work. The ending is meant to make the audience feel good, with a final scene of Wain making art in a gorgeous library with large windows, before roaming away into a vast grassy field outside of the hospital.

While it is comforting to think that Wain was able to end his life in relative peace, some viewers may be left surprised by the lack of critique regarding the medical establishment at the time. There is relatively little concern regarding society’s treatment of the mentally ill Wain and of course almost no acknowledgement of anyone who lacks his privileges as a white man. One of Wain’s younger sister’s Marie, played by Hayley Squires, suffers similar symptoms to him and is shown being driven away in a black cage to an insane asylum. We do not see her character again, but are briefly informed by Coleman that she died some time after being admitted.

There are still good reasons to watch this movie. The acting, as expected from multiple A-listers, is fantastic. The setting and cinematography are also beautiful, with many vibrant colors, likely meant to be reflective of Wain’s artwork. But best of all; there are so many cats!

draw cats almost exclusively. The film “The Electrical Life of Louis Wain” covers the story of the artist, who is largely credited for the normalization of cats during his time.