Last fall, an incident in a Hamline classroom brought the rights of adjuncts to the forefront of many discussions. Still, adjunct professors are not seeing any policy change. Early this week, a Hamline adjunct professor called attention to a nationwide tension within higher education in a bold display on his office door.

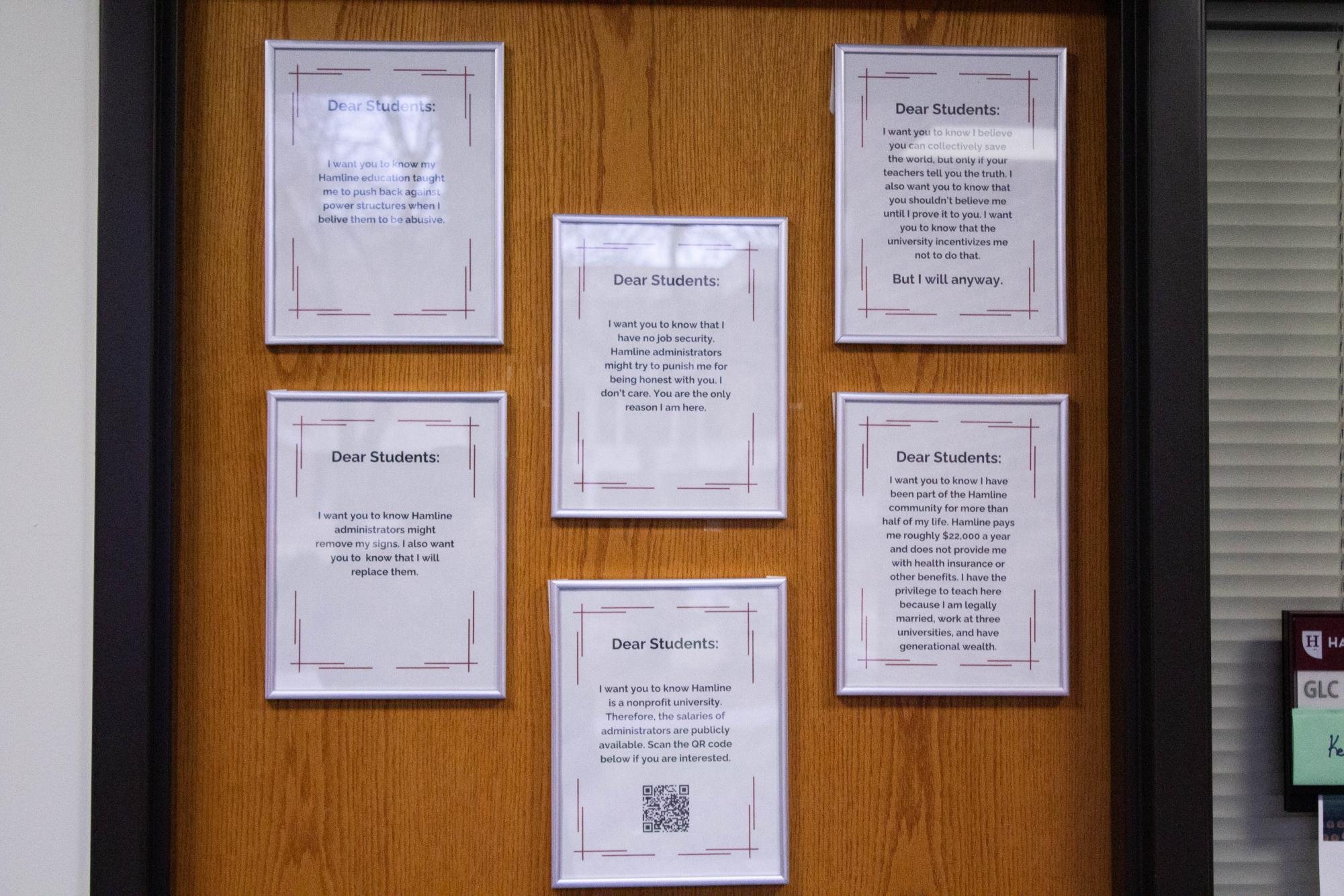

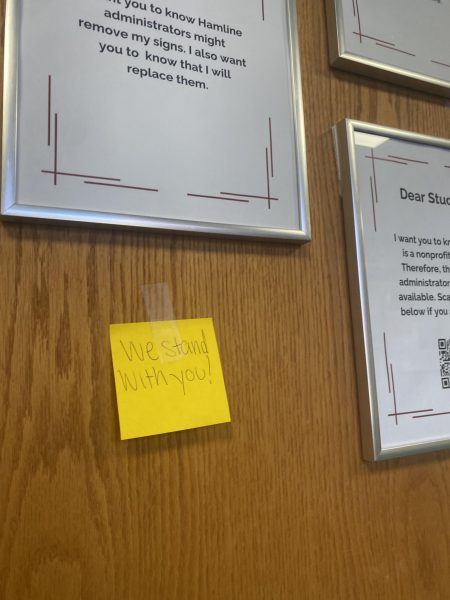

Vulnerable adjunct professors are not unique to Hamline, but they are well represented here. The widely-reported choice not to renew an adjunct’s contract last year has been a key part of Hamline’s role in an ongoing lawsuit. Early this week, Adjunct Professor Kevin Schwandt drew new attention to the issue by voicing his frustration in six signs mounted to the door of his office. Behind other doors, new negotiations are already underway.

“I was taught that John Wesley quote over and over and over again: that one about doing all the good you can and in all the ways you can. I tried one way, tried it several times … so [posting signs] is another thing that I’m trying,” Schwandt said. “And it doesn’t have to be like this. It truly does not have to be like this.”

An adjunct professor’s contract lasts for a single semester. This comes in stark contrast to tenure, a unique feature of higher education in which more senior professors are granted a nearly irrevocable job security. Despite their precarious position, adjunct and non-tenure-track professors at Hamline regularly stay in their roles for multiple years.

Schwandt has been an adjunct professor at Hamline for six years and is a 2002 Hamline alumni. Schwandt teaches first year writing classes in the English Department, and despite many attempts at creating a stable job for himself at Hamline, he has been met with resistance from administrators.

“I think that I just reached a point … where I sort of came to the conclusion that I wasn’t getting anywhere, and I had two remaining options,” Schwandt said. “One is to just give up and leave, and the other one was to do something to draw attention to it.”

Adjuncts at Hamline are not alone in feeling tensions as they seek job stability and benefits in their roles. According to English Professor Mike Reynolds, this issue is systemic in higher education on a much larger scale.

“There’s been a constant move across the country to move towards temporary labor and not to have an institutional investment in full time faculty,” Reynolds said. “You don’t even need to call it an erosion of tenure; I think it’s just an erosion of labor.”

In 2014, Hamline’s adjuncts were among the first faculty in the state to unionize as part of a national campaign by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). Although their union, SEIU Local 284, could not be reached for comment at press time, multiple faculty sources confirmed that a new contract negotiation is in progress. Though they aim to address many of the same issues, Schwandt’s actions are independent of the union.

“Good for him,” Professor Richard Pelster-Wiebe said in response to the signs on Schwandt’s door. “It’s really commendable what that professor [Schwandt] is doing, because I do think that they’re taking on considerable risk.”

Pelster-Wiebe—the director of Hamline’s Creative Writing program—came to Hamline as an adjunct professor in 2015 and took part in that year’s contract negotiations. Though he has since become a full-time employee of the university, in contrast with his responsibilities as a program director, Pelster-Wiebe is not a tenure-track professor either.

“[Many] classes in our programs are taught by adjuncts,” Pelster-Wiebe said. “There’s a need for a full time faculty member. It’s undeniable, but it just doesn’t seem that it’s coming. So, instead, there’s this kind of reliance on the adjunct workforce.”

Faculty attempted to avoid this issue when writing visiting professors into the faculty handbook as a temporary, not permanent solution to a lack of full time faculty.

“Visiting Faculty should not be used in place of tenure-track faculty where a continuing need for a tenure-track faculty is established,” section 4.5.3 of Hamline’s faculty handbook reads.

Despite this clarification in the handbook, Reynolds acknowledges the loophole that has allowed administration to keep visiting professors on for years without guarantees of security or benefits.

“This visiting [professor title] … I feel like it’s a loophole that we weren’t smart enough to define a term limit, no more than three years,” Reynolds said. “I get frustrated. Because there’s a loophole doesn’t mean that those with the most authority to make the decision should be doing so.”

The message on Schwandt’s signs is directed to the student population of Hamline: the community that Schwandt hopes will absorb the example of self advocacy.

“Hamline has a tradition of activism, and there’s a lot to be activated about,” Schwandt said. “I certainly don’t think that I have the worst problems in the world, but I also believe that you have to make change where you are, and I am here.”