Just a little over a week before the Oscars, the Society of Physic Students (SPS) hosted a watch party for the most nominated movie of 2023, “Oppenheimer.” Students and professors alike crowded in GLC on Sat. March 2, munching on soft-shelled tacos and various desserts from El Burrito Mercado.

This is the organization’s first event of the semester, where they collaborated with the Hamline University Programming Board (HUPB) to draw in a wider audience. With an event being planned during the day on a weekend, they wanted to use this as a chance not only to entertain on-campus students but to spark an important conversation in the world of science and ethics.

“We wanted to not only have an event where people could watch a movie relating to physics, because [Oppenheimer] was an atomic physicist, but we wanted to sort of create a discussion around the ethics of using these weapons, both for the greater good in the context of science and technological innovation,” Vice President of SPS senior Fadhimah Mohamed said.

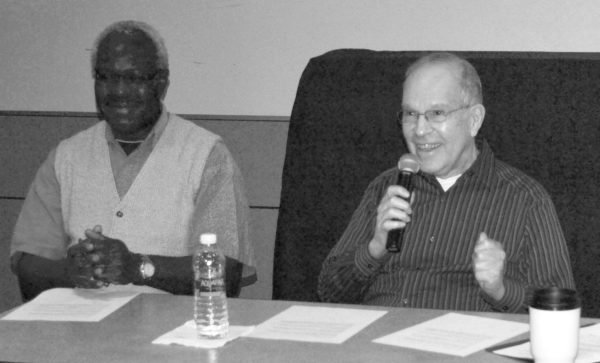

To provide a wider lens for this discussion, SPS invited three Hamline professors to participate in a panel discussion held at the end of the film. Among the panelists were Professor Suda Ishida, who holds strong opinions about “Oppenheimer” and its romanticization of a devastating tragedy for the Japanese people; Professor Jerry Artz, with firsthand experience visiting the Trinity testing site, where the first atomic bomb was tested; and Professor Sam Imbo, who was enthralled by the film’s ability to capture the unique character that Dr. J Robert Oppenheimer was.

The panelists were given a set of questions before the film began, allowing them to gather their thoughts before sharing them with the students who lingered after the movie had ended. The President of SPS began the talks by introducing each of the professors and asking them the first question.

“I was really surprised on the emphasis that was placed upon the trial of Oppenheimer, it was something that I really just didn’t expect at all,” Artz said. “I mean, here spoke the father of the atomic bomb … I’ve been at the Trinity site, and it is still radioactive till this day, and you’re standing on glass because the heat from the explosion actually turned the sand into glass, and to see that and go back in time.”

For scientists, the scientific aspect of the film was impressive, even providing an accurate representation of explosions, including the blinding lights, delayed boom and the aftershock. However, the film is filled with plenty of known scientists, possibly too many that it can be overwhelming for scientists and non-scientists alike.

One of the big ideas brought up by all three panelists was the sheer lack of representation of the other sides of this American Prometheus tale. Ishida points out the fact that the only physical representation of the devastating effects of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a two-second clip where Oppenheimer stepped on the burnt corpse during a traumatic hallucination.

Even so, the film only mentions the fact that the creation site, known as Los Alamos, was taken from the Navajo people. It does not seem to acknowledge how the land is now uninhabitable due to the long-lasting radiation from Trinity. However, even in the film’s three hour runtime, there are only so many perspectives that can be shared.

“A point about viewpoints, is that this is just one movie, and we should certainly watch it, realizing it is being made an American made for primary American audiences, and then you can travel the world,” Imbo said.

Along with this idea of representation is that the impacted people should be making these films from their own lens, instead of a watered-down perspective of an outsider. However, despite this lack of acknowledgment, there is something valuable about watching a film from the perspective of “Oppenheimer” alone.

When discussing the intricacies of The Manhattan Project and Oppenheimer’s reasoning, Artz brings up the fact that he was a Jewish man during the Holocaust. A line from the film that truly emphasizes the importance of this is that in an argument, Oppenheimer says, “It’s not your people they’re herding into camps. It’s mine.”

However, it is this idea of moral reasoning that further complicates the issue at hand. Oppenheimer joined the project when it was to be used against the Germans and was so deeply involved due to his religious identity that by the time their target shifted to the nearly-surrendered Japanese, the question of whether he should have continued with the creation was at odds with his need for innovation.

“When we think about technology, oftentimes you tend to have this myth that it will be only one way, which is progressiveness. So if you’re not moving forward, we’re not advanced enough and we’re going to get behind,” Ishida said, introducing the topic of the pros and cons of such important technological innovation.

The panel soon dove into a discussion about the similarities of technological improvement today with AI and the creation of these weapons, though they made sure not to undermine the tragic impact that the atomic bomb had on hundreds of thousands of people and their lands. This impact on both the people and the land makes a key line repeated throughout the film true.

“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”