The Reactor in our Backyard

How nuclear power might be changing in the years to come

October 4, 2022

An article from nature.com came across my desk a few weeks ago announcing that France is experiencing dramatically diminished capacity of its nuclear power plants, with about half of the reactors being inactive.

This is notable given that France has functioned as world leader in nuclear power per capita, and has gained significant funds through its energy exports.

I was curious to learn a little more about the current state of nuclear power, and I found that the issue is not restricted to France. The issue may soon be changing on our side of the pond, and depending on votes this fall — perhaps even in our own state.

The reason for this potential change comes down to a moratorium passed nearly three decades ago. The Minnesota legislature decided in 1994 that no new nuclear power would be added in our state.

However, the issue has been brought up for debate, with the campaigning politicians speaking of its permanence (or lack thereof).

In the middle of climate and energy concerns, many are reevaluating the role of nuclear energy in Minnesota.

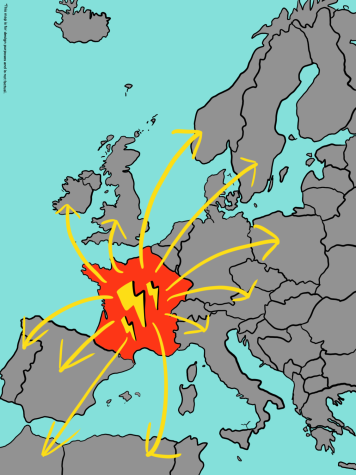

Interestingly, the issue does not restrict itself to one side of the political aisle, and has supporters coming from left, right and center. However, this is not to say the support is unanimous — far from it. Nuclear power carries an element of risk, and the minds of some detractors recall Three Mile Island or Chernobyl.

Granted, the cause of these can be traced to broken protocols or equipment failures, but the fact that it was not “supposed” to have happened is cold comfort to the communities permanently affected by the tragedy.

These legitimate concerns, though, represent risks that can be mitigated by careful planning, and weighed against the tremendous benefits offered such as those to the climate (through reduction of greenhouse gases) and the economy (through energy independence).

To reference France again, nature.com explains that the country’s nuclear prominence has provided a means to light up their own cities and remove fossil fuels, all while generating $3 billion dollars per year in energy exports. As we evaluate this ticket to clean energy, we may find the riskiest aspect is, in fact, delaying its use.

These matters are not merely theoretical. Should the moratorium on nuclear energy be lifted in Minnesota, there may be a new reactor in driving distance. Granted, it likely will not be functional anytime soon, but the policies of today create the world of tomorrow; a world that we will be living in.

What then, is the best option? Does a “best” option even exist?

In order to find an answer to these questions, it might be most helpful to first look at how we arrived at our nuclear energy dialogue. The issue of nuclear power has been contested as long as nuclear power has been considered as a possibility — and the controversy around this topic from decades past frames discourse today.

I decided to look into this long-standing discourse as I figured this would be a nice topic to cover in a column. However, the rabbit hole continued deeper the longer I probed, spanning into history, science, politics, international relations and thermonuclear war.

After enough research, it became apparent that the multidimensionality of this rabbit hole — perhaps more appropriately described as a labyrinth — could not be covered in a single pass.

In my next column, we will examine this historical dialogue, and what it can mean to us. Regardless of one’s position in society — whether an environmental steward, informed voter, or area resident — it is clear that nuclear power is an issue worth giving some serious thought.