Whispers on the walls

A brief examination of campus graffiti

March 30, 2022

In a dusty, cobwebbed corner of a gated off storage space on the third floor of West Hall, there’s an Instagram handle written in black ink on a long-forgotten whiteboard. As a freshman, I stood next to a stack of unused filing cabinets and looked at the whiteboard for a long time. The next morning, I messaged the account.

The account belonged to Olivia Stevens–a current U of M student who just so happens to have been friends with one of our own reporters in high school. Two years earlier, on the last day of a Hamline writing camp, she was poking around campus and, like me, found herself in the storage space. Not thinking anything would come of it, Stevens wrote her Instagram handle on a whiteboard before leaving.

“I don’t personally care about gaining random followers,” says Stevens, “I just thought the idea of someone seeing it in that random room might be worth a laugh.” To me, it was worth more than a laugh. In a small way, Olivia changed my life. My world shrank that day as I stood among the stacks of office chairs and tables, staring at her handwriting.

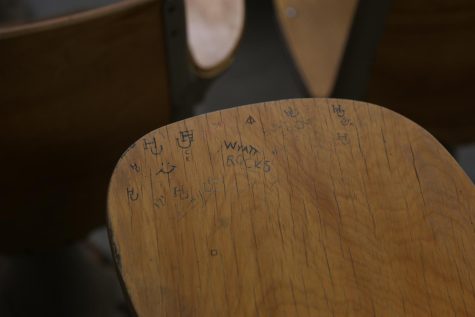

For the purposes of this article, I’m using a broad definition for graffiti, including anything from dry erase markers on whiteboards to Sharpie markings or carvings in bathroom stalls and desks. It’s garnered an unfortunate reputation as a childish act of vandalism– the senseless effort of damaging school property with doodles. At best, that viewpoint is a shortsighted oversimplification. At worst, it’s a dangerous misunderstanding.

“From an anthropological perspective, [graffiti] tells us something important about human concerns, inventions, imaginings, creativity, spatial and temporal understandings, and the like,” says Professor Matt Sumera of the Anthropology department. “An analysis of graffiti, provided it is always situated within a broader discussion of systems of power and cultural meaning, can tell us a great deal about how people negotiate a range of divisions, identities, and claims.”

Some campus graffiti is sophomoric– phrases like “WYATT ROCKS”, “HU Baseball is garbage!” carved among genitals and the universal ‘Cool S’–but why shouldn’t it be? Some of us are, after all, sophomores.

Some graffiti offers genuine critiques on the world. On one desk, the Einstein quote “It’s a miracle curiosity survives higher education,” can be found etched near the words “I don’t get this class.” Another student’s reminder to themselves, “Ask about gravitational lensing,” is eternally memorialized in a forest of hastily scrawled equations doubtlessly drawn moments before a pop quiz. There’s even been a lengthy, albeit informal debate on the merits of different presidential candidates raging in one stall of a Drew Science bathroom for over four years.

Unfortunately, graffiti is also commonly used for hate speech. This has been regrettably illustrated by a string of racially and ethnically motivated incidents on campus in the past few years. Wandering through Hamline’s older classrooms and bathrooms, it’s not hard to find more. Any form of hate based graffiti should be immediately documented and reported to Public Safety. If possible, it’s best practice to temporarily obscure the graffiti until it can be appropriately dealt with to avoid the retraumatization of marginalized students who might happen upon it.

Whittling hate symbols or slurs into a wooden desk isn’t the act of a bored student, it’s the conscious and deliberate messaging of white supremacy. In simpler terms, it isn’t a graffiti problem, it’s a racism problem.

Perhaps most importantly, graffiti can be incredibly beautiful. Until it was erased a few weeks back, a dazzling mural of flowers and surreal, fantastical beasts had been growing on an unused GLC whiteboard.

“I view [graffiti] as entirely authentic as it comes directly from the people, with no level of censorship or filtration impeding upon it, and also wonderfully valuable in its temporality,” says Sophomore Max Ridenour, “Graffiti, when created in the spirit of genuine constructive expression, keeps an environment dynamic and vibrant.” It’s raw, unadulterated self-expression, and an important art form.

Graffiti also transcends time in a given space. A carved L+M encased in a heart in Old Main could well have been there since before the invention of the airplane. Who were L and M? Where are they today?

If nothing else, graffiti reminds us that we’re not alone–that other people, with their own complex thoughts and emotions, have been through the same spaces as us. Past students are whispering to you with their penknives and Sharpies. Listen to them. Whisper back. Life is short and undergrad is even shorter–make art, make history, even if that just means carving pictures of genitals in a bathroom stall or writing your Instagram handle on a long-forgotten whiteboard.